This post first appeared in American Prospect and appears here by special permission.

In 2014, California Governor Jerry Brown inducted community organizer Fred Ross Sr. posthumously into the California Hall of Fame, where he joined a long list of other luminaries that includes the likes of Amelia Earhart, César Chavez, Steve Jobs, and Jackie Robinson. Ross may be the least-known figure among the inductees, but he is certainly one of the most influential.

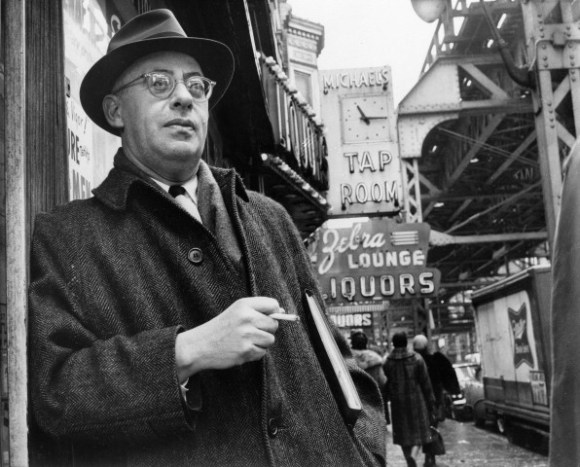

This anonymity was intentional on Ross’s part. He believed that organizers should always be behind the scenes. As organizer and journalist Gabriel Thompson explains in this fascinating biography, Ross “spent his life pushing people to lead—in living rooms, in union halls, on picket lines—and in doing so he pushed himself right out of the spotlight.”

Ross was an “unsung hero,” according to author Carey McWilliams, the former long-time editor of The Nation, who described his friend Ross as “a man of exasperating modesty, the kind that never steps forward to claim his fair share of credit for any enterprise in which he is involved.”

Thompson’s well-written and revelatory book—based on extensive archival research and interviews with many of Ross’s coworkers, friends, family members, and students—may finally help give Ross (1910-1992) the credit he is due.

Many of his strategic innovations have become standard practice among organizers. Any organizer who has conducted a voter registration and turnout campaign, held a house meeting to recruit grassroots activists, or launched a boycott to pressure a powerful person or institution, owes a debt of gratitude to Ross.

Thompson describes Ross as “an idealist who wasn’t afraid to get [his] hands dirty.” Ross dedicated his life to fighting racism, discrimination, and other injustices by organizing working people to help themselves by building powerful grassroots organizations. For over five decades, he helped build community organizing groups, played a key role in building the United Farm Workers (UFW) union, and built bridges between labor, religious, civic, and neighborhood organizations.

Years before the feminist movement of the 1970s, Ross was a pioneer in recruiting and training women as leaders of grassroots organizations. Long before Black Lives Matter, he led campaigns against police brutality and racism. He helped catalyze the upsurge of political activism within the Latino community that has reshaped American politics.

To the extent that Ross is known outside of progressive circles, it is in his role as the person who recruited and trained Chavez as an organizer. But on this score, Thompson explodes some myths and even raises troubling questions about Ross’s relationship with the UFW’s legendary founder.

Ross once said, “A good organizer is a social arsonist—one who goes around setting people on fire.” That’s what Ross did: listening to people with grievances, and helping them channel their anger into constructive activism that improved the lives of millions of Americans, most of whom never knew his name. He trained thousands of organizers and led countless campaigns to better humankind. Ross’s goal was to empower people to vote, improve their neighborhoods, challenge inhumane working conditions, and foster coalitions of good will across race and religion.

Ross was an unlikely activist.

Ross was an unlikely activist. He was born to a conservative middle class family, grew up in Los Angeles, and attended the University of Southern California (USC), a bastion of conformist frat-boy culture. In fact, while in college the tall, handsome Ross spent much of his time lifting weights at the beach. But the social and economic upheavals of the Depression radicalized him and led Ross in a different direction.

At USC, Ross became friends with New Yorker Eugene Wolman—a communist and a Jew, both new affiliations to Ross. Wolman expanded Ross’s social and political horizons. He got Ross involved in radical campus activism, and encouraged him to take courses with USC’s handful of leftist professors, to read eye-opening works of social realism like James Farrell’s novel Studs Lonigan, and to absorb the radical ideas of Upton Sinclair, the socialist writer who ran for governor in 1934 on a platform to “end poverty in California.” In 1936, Ross and Wolman drove to Orange County to support striking Mexican American citrus workers. There they encountered USC football players who functioned as security guards and deployed baseball bats to beat the strikers. That was Ross’s first exposure to California’s semi-feudal farm labor system. Three decades later, he would play an important role in organizing farm workers to overturn that structure.

After he graduated from USC in 1936, Wolman went to work at a Los Angeles can company intent on organizing its workers. The next year he joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain to help the Spaniards resist General Francisco Franco’s fascist army. Within a few weeks, Wolman was killed in combat. Thompson suggests that Ross’s guilt about staying in the U.S. while his friend made the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of his leftist values spurred him to devote the rest of his life to fighting for social justice.

Ross was a pragmatist with a great curiosity, so to find why people who worked also applied for welfare, Ross secretly took a job tying carrots in the fields.

Ross had planned to find a teaching job. Instead, he went to work as caseworker for the State Relief Administration (SRA) in rural Riverside and Indio. He heard other caseworkers complain that many of their clients were working illegally while collecting welfare. When he saw some of his clients working in the fields, he was initially outraged that they had lied about being out of work. Ross was a pragmatist with a great curiosity, so to find why people who worked also applied for welfare, Ross secretly took a job tying carrots in the fields. After working 12 hours, he had only earned 84 cents. This experience opened his eyes to the exploitation of California’s farmworkers and the need for government assistance. When he relayed the story to his co-workers, he expected them to share his sympathies. Instead, his supervisor penalized him for his “unprofessional behavior.” Ross also learned that the SRA insisted that its clients take any job that came along, which included working as strike-breakers for California growers—something he would learn much more about a few decades later.

Ross’s most profound learning experience during his short stint with the SRA was his encounter with a man he called “Milligan,” whom he described as a “plain, ordinary, working stiff who wasn’t shiftless and wasn’t stupid, and gave it his best shot for his whole pain-filled life, and still couldn’t make it.” Ross decided he would write the “Great American Depression Novel” with Milligan his central character. But, as Thompson explains, except for his detailed reports and journals about his organizing experiences, Ross’s efforts to write the novel, as well as an autobiography, came to naught.

Ironically, though, Ross did play a role in influencing the people that John Steinbeck wrote about in what many consider the greatest Depression-era novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

After leaving the SRA, Ross went to work for the federal Farm Security Administration (FSA), a New Deal agency designed to help displaced agricultural workers and small farmers. In 1939, he became the manager of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Arvin Migratory Labor Camp, located in an isolated area outside Bakersfield. His mentor in the FSA regional office, Robert Hardie, urged Ross to make the camp (in Thompson’s words) “a place of dignity, a safe haven where Dust Bowl migrants could begin rebuilding shattered lives.”

Ross helped the families organize a residents’ council, a newspaper, and a co-op store. He was the only manager of 19 such camps in California who challenged the accepted practice of racial segregation. Unlike the miserable camps run by the growers, the Arvin camp provided hot showers, free medical care, a library, and clean drinking water. Steinbeck visited Arvin and used it as the model for the Weedpatch camp in The Grapes of Wrath. (In the award-winning 1940 film version, the Weedpatch administrator, played by Grant Mitchell in rimless glasses and wearing white pants and sweater, looks conspicuously like FDR). Ross met Woody Guthrie at Arvin while the folksinger was touring the camps to support workers’ union drives, and escorted Eleanor Roosevelt around Bakersfield’s slums to show her that the appalling conditions described in The Grapes of Wrath were not exaggerated.

Watching these desperate farmworker families practice self-government during his two years at Arvin strengthened Ross’s faith in the power of ordinary people to change their own lives. While running the Arvin camp, he supported the efforts of farmworkers in the surrounding area to organize a union (a violation of FSA rules, which mandated that administrators remain neutral), led by a militant CIO union affiliated with the Communist Party and other left-wing activists. He permitted union organizers in the campus and allowed pro-union articles to appear in the Tow Sack Tattler, the camp newspaper. He watched as local growers hired vigilantes to break the heads of strikers while local police and sheriffs (and judges) looked the other way or, in some cases, participated in the violence. Ross saw first-hand the “rural civil war” that his friend Carey McWilliams, a muckraking writer and activist, described in his 1939 exposé Factories in the Fields.

During World War II, amid widespread anti-Japanese hysteria, Ross ran a large government-sponsored internment camp for Japanese Americans at Minidoka, Idaho, trying to help the prisoners make the best of an oppressive situation. That experience taught Ross, writes Thompson, “how quickly a democratic country could abandon its principles.” He then moved to Cleveland to work with the War Relocation Authority, helping thousands of Japanese Americans get jobs (primarily in the defense industry) and housing so they could get out of the camps. He helped challenge the discriminatory practices of employers against Japanese workers.

Rather than do things for people, he recognized the importance of helping people—agitating them, if necessary—to do things for themselves.

Ross’s experiences in Arvin, Minidoka, and Cleveland inflamed his sense of outrage at the mistreatment of American citizens, but he was also impressed by their resilience. As Thompson relates, Ross began shifting his outlook from that of a social worker to that of an organizer. Rather than do things for people, he recognized the importance of helping people—agitating them, if necessary—to do things for themselves. This became Ross’s calling and his guiding principle for the rest of his life. He pledged to devote his life to bringing about “full democracy in race relations.”

But how could Ross earn a living? Ross drew on his extensive network of contacts to create a job for himself as a community organizer in California’s Latino barrios. After the war, with support from the liberal American Council on Race Relations, he spearheaded eight Civic Unity Leagues in California’s conservative Citrus Belt, bringing Mexican Americans and African Americans together to battle segregation in schools, skating rinks, and movie theaters. Through voter registration drives and community organizing, Ross rallied parents to fight the practice of segregation in local schools.

In 1946, Ross helped local Mexican American and African American residents build an unprecedented and powerful voter registration and turnout campaign in the tiny Riverside County town of Casa Blanca. With enormous attention to detail, Ross trained residents to go door to door to register voters. He met regularly with his volunteer activists to discuss which tactics had worked and which hadn’t. He stumbled across a tactic that he would later use extensively and teach to generations of organizers—the use of intimate house meetings to get people to talk to their friends and neighbors about their grievances, to identify potential leaders, and to build widening networks of activists.

Ross left as little to chance as possible, reflecting his view that “the incidentals make up the fundamentals.” On Election Day, the Casa Blanca Unity League overwhelmed the unsuspecting politicians with a remarkable get-out-the-vote mobilization. Some activists volunteered to drive voters to the polls. Others babysat at people’s homes so the parents could vote. They even had parish priests visit people on Election Day to make sure they cast their ballots. They replaced a racist city council member with a candidate who pledged to help the low-income residents of Casa Blanca.

Ross would utilize this strategy throughout his career and teach it to thousands of others who, in turn, relayed the lessons to others. Indeed, the use of Ross’s ideas—by community organizers and campaign operatives, including those working for Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign—would dramatically change American politics forever.

Although Ross was most comfortable with grassroots organizing and electoral campaigns, he also saw the value of using litigation to win victories. In 1946, as part of a community organizing effort against local school boards, Mexican American residents sued several Orange County school districts for segregating Mexican and Mexican American students into separate “Mexican schools.” The following year, in Mendez, et al v. Westminster School District, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that this arrangement was unconstitutional, a landmark legal victory. It set the precedent that foreshadowed the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, overturning legal segregation in American schools.

Based on these successes, Ross came to the attention of Saul Alinsky, the Chicago-based community organizer who, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, had built a successful coalition of unions, civic groups, and religious organizations called the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council, had written his organizers’ handbook Reveille for Radicals (1946), and was looking to expand his experiments in grassroots democracy through a network of local groups called the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). In many respects, Alinsky (who was only a year older) and Ross had been working along parallel lines. They had never met, but Ross was familiar with Alinsky’s book. In 1947, Alinsky hired Ross as the IAF’s West Coast organizer. As Thompson recounts, Alinsky wrote to a friend: “I have hired a guy who I think is a natural for our work. It will really be the first time that I have had a capable associate who understands exactly what we are after.”

Even so, they differed in many ways. Alinsky was flashy, boastful, and tired quickly of the daily grunt work of day-to-day organizing. Ross was quiet, earnest, and a stickler for details. Alinsky loved “the people” but wasn’t that interested in the daily lives of the folks he was organizing. Ross empathized with the suffering of ordinary people, was a patient and good listener, and took the time to get to know the people he worked with and for. Mostly importantly, Alinsky—who had close ties to liberal philanthropists and Catholic Church leaders—was a good fundraiser, and Ross was not. His partnership with Alinsky freed Ross to focus on organizing without worrying about his paycheck, but this trait would later come back to undermine his organizing efforts.

Together they fought for fair housing, employment, and working conditions.

Ross began working in the Latino barrio of East Los Angeles to build what became the Community Service Organization (CSO). The founding leaders of the CSO included members of the steelworkers, clothing workers, meat cutters, and other unions. They formed the core of CSO’s early leadership who built a powerful coalition that included the NAACP, the Japanese American Citizens League, the Catholic Church, and the Jewish community. Together they fought for fair housing, employment, and working conditions.

One of CSO’s biggest victories came in the wake of a severe beating of seven men (five of them Latinos) by Los Angeles police on December 25, 1951, known as “Bloody Christmas,” which left the victims with broken bones and ruptured organs. Pressure from CSO forced the LA Police Department—which routinely harassed and abused blacks and Latinos—to investigate the incident. The CSO helped build the case against the abusive cops by documenting complaints and keeping up public pressure in the media. This eventually resulted in the unprecedented indictment of eight police officers—the first grand jury indictments of LAPD officers and the first criminal convictions for use of excessive force in the department’s history. In addition, the LAPD suspended of 39 cops and transferred another 54 officers.

In 1949, after building a powerful voter registration effort among Latinos, blacks, and whites, the CSO helped elect one of its leaders, Ed Roybal, to the Los Angeles City Council, in a landslide victory. The campaign added 17,000 new voters in what Thompson calls a “grassroots machine.” Roybal was the first Hispanic elected to that body and in 1962 became the first Latino from California elected to Congress, where he served with distinction for 30 years.

After his success in Los Angeles, Ross determined to build CSO into a statewide organization with chapters in the Mexican American barrios in California’s major cities.

In 1952, while Ross was building the CSO chapter in San Jose, a Catholic priest and a public health nurse led him to César Chavez.

In 1952, while Ross was building the CSO chapter in San Jose, a Catholic priest and a public health nurse led him to César Chavez. As Thompson recounts, this encounter, which occurred on June 9, 1952, “has been repeated so many times by so many people that it has taken on the power of a myth.” Thompson does a superb job of separating myth from fact, based on extensive interviews and archival research.

After Chavez’s father lost the family’s small farm in Arizona during the Depression, the Chavez family joined the roughly 300,000 migrant workers who followed the crops to California every year. The family often slept by the side of the road, moving from farm to farm, from harvest to harvest, living in overcrowded migrant camps. César attended 38 different schools until he finally gave up after finishing the eighth grade. Chavez spent two years in the Navy during World War II. Returning home, he married, moved to San Jose’s Mexican barrio (known as Sal Si Puedes—“Get Out If You Can”) and took whatever jobs he could find in the nearby fields or lumberyards.

Chavez at first avoided meeting with Ross, thinking he was just another do-gooder white social worker or sociologist curious about barrio residents’ exotic habits. Chavez invited some of his street-tough friends to the meeting, intending to humiliate Ross. One widely repeated account of this meeting, perpetuated by Chavez himself, has Chavez prearranging a signal with his friends. If he shifted his cigarette from his right hand to his left, they would tell Ross it was time to leave. Chavez’s brother Richard, however, told Thompson that this story was fiction.

But the truth is that it turned out to be a fateful meeting. Chavez was mesmerized by Ross’s stories of how Mexican Americans had organized, registered voters, and won victories in other cities. “The more he talked, the more wide-eyed I became,” Chavez once recalled.

In later interviews, Ross recounted that he went home that night and wrote in his journal, “I think I’ve found the guy I’ve been looking for.” This statement has also been repeated often, but Thompson reveals that it, too, is a myth.

Ross trained Chavez, first as a CSO leader, then as one of CSO’s organizers, and eventually as its statewide director. Chavez said, “As time went on, Fred became sort of my hero. I saw him organize and I wanted to learn.”

Ross also trained a young teacher named Dolores Huerta, and Gilbert Padilla, a spotter in a dry cleaning establishment, as CSO leaders. Chavez, Huerta, and Padilla eventually joined forces to build the UFW.

By 1955, the CSO had 22 chapters across the state and had racked up impressive victories. Thompson writes: “Over its lifetime, CSO amassed a long list of tangible accomplishments—registering hundreds of thousands of voters, electing a handful of politicians, forcing city officials to pave streets and crack down on police brutality—but what many members recalled, decades later, was their transformation into individuals with too much political self-respect to be ignored or abused.”

But Ross never found a formula to sustain CSO financially. Alinsky raised enough money to support Ross’s efforts for three years, but after that, he was on his own. Ross recruited backers among some unions, foundations, and wealthy liberals, but he was ambivalent about asking CSO members to pay dues to support the staff. Eventually, most of the CSO chapters fell apart or were taken over by middle-class opportunists who lacked the same passion for grassroots organizing.

When the organization’s leaders opposed Chavez’s recommendation that CSO embark on an effort to organize farmworkers, Chavez quit and, with Huerta and Padilla, started what would soon become the UFW.

Ross left California in 1964 to work briefly in Arizona and then to start a new IAF-sponsored project in Syracuse, New York, using funds from a new federal anti-poverty program to organize in that city’s African American community, while training social work students at Syracuse University to become organizers. Ross faced criticism from some of the New Left students who thought that community organizing should lead to revolution, not more stop signs, job training programs, and new voters. As Thompson relates, some of them also bristled at Ross’s stern discipline about the nuts-and-bolts of organizing, while others appreciated Ross’s efforts to tame their individualistic let-it-all-hang-out ethic. But the Syracuse initiative was soon thwarted by the city’s business and political power structure, which maneuvered to get its federal funds withdrawn.

The collapse of the Syracuse program was fortuitous in the end, because it led Ross back to California after Chavez asked him to join the UFW staff.

During his 15-year tenure with the UFW, Ross trained 2,000 organizers who led worker strikes and consumer boycotts in every major U.S. and Canadian city, leading to major gains for farmworkers.

Ross’s insistent—some would say fanatical—discipline helped strengthen the burgeoning movement. The union not only had to mobilize farmworkers in the grape, lettuce, and strawberry fields, it also had to do battle with local sheriffs and judges, not to mention the Teamsters union, which had a sweetheart deal with the growers and were not shy about using violence to intimidate workers loyal to the UFW. Ross’s organizational skills, Chavez’s charismatic leadership, and the commitment and resolve of the UFW’s leaders, low-paid staffers, and volunteers, kept the movement advancing in the midst of all these obstacles.

Ross’s big role with the UFW was training the national boycott staff. It was no easy task to mount a boycott in every major American city, staffed mostly by Mexican American farmworkers who had never been outside California or Mexico, and who typically showed up in a strange city with only a few dollars in their pockets and the names of a few supporters to contact. Eventually, the boycott became a popular cause among college students, liberal religious congregations, and labor unions. Many Americans got used to keeping table grapes and Gallo wine off their shopping lists. The boycott was critical in forcing the growers to come to the negotiating table and agree to sign path-breaking collective bargaining contracts with the UFW. The contracts dramatically improved farmworkers’ income, working conditions, and housing, made it possible for their children to stay in school, and helped turn Chavez into a national figure who inspired many Mexican Americans to take pride in their ethnicity and to fight for more rights and political power. The boycott was perhaps Ross’s most impressive organizing achievement.

But as the UFW became stronger, winning more strikes and contracts, it faced a problem that had been bubbling below the surface for years.

Ross was also instrumental in helping the UFW forge close political ties with elected officials, including Senator Robert F. Kennedy and California Governor Jerry Brown. In 1975, with Brown’s help, the UFW pressured the state legislature to adopt the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, a major breakthrough because agricultural workers were not covered by the National Labor Relations Act passed during the New Deal.

But as the UFW became stronger, winning more strikes and contracts, it faced a problem that had been bubbling below the surface for years. Despite his public image as a modest, saint-like figure, Chavez’s success changed him. He became a control freak who was paranoid about any opposition to his leadership within the union. As the union grew, his paranoia worsened. He came to view some loyal leaders and staffers as “traitors.” Chavez purged talented leaders, staff, and volunteers who challenged his ideas and authority. The UFW spiraled into chaos. The union put fewer resources into organizing workers in the field and failed to win more elections. Growers did not renew contracts. Membership declined. Working conditions and pay worsened. It was a tragedy of major proportions.

This story has been told before—particularly in Miriam Pawel’s The Crusades of Cesar Chavez and Marshall Ganz’s Why David Sometimes Wins—but Thompson’s telling reveals Ross’s troubling role as an enabler of Chavez’s worst traits.

Thompson makes a strong case that because Chavez respected him so much, Ross may have been the only person who could have challenged the union leader and thwarted his self-destructive behavior. But Ross kept quiet. It is possible that Ross, like many others, put Chavez on a pedestal, beyond criticism.

It is also possible that Ross’s tolerance of Chavez’s fanaticism mirrored some of his own tendencies. Ross viewed organizing as an all-or-nothing calling. He was fully committed to the movement and he expected all his organizers and volunteers to share his level of dedication. He chose not to see or understand the emotional toll that organizers’ grueling schedules took on their lives. He did not believe in the concept of “burnout.”

Finding a balance between work and family is an ongoing dilemma, one that is particularly acute for political organizers and activists, both in Ross’s day and today. Ross was, by all accounts, an absent husband and father. He was constantly working, traveling, and attending meetings during days and nights. He was married and divorced twice and, according to Thompson, had at least one brief affair while still married. Even when his second wife was seriously ill, and occasionally hospitalized, she was essentially on her own, without much support from Ross. He was also distant from his three children, although late in life he became closer to his youngest son, Fred Jr., who followed in his footsteps as an organizer with the UFW, the Industrial Areas Foundation, SEIU, and currently the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

In the 1980s, Ross joined Fred Jr., then Executive Director of Neighbor-to-Neighbor, to train yet another generation of organizers to challenge U.S. aid to Nicaragua’s right-wing contras and to stop aid to the brutal Salvadoran military.

His work with Neighbor-to-Neighbor, which expressed solidarity with Central America’s revolutionary movements, was a departure for Ross. During his organizing life—much of which occurred during the Cold War—he had eschewed political affiliations and ideological pronouncements, although he was clearly sympathetic to radical causes. He was often redbaited and followed by the FBI, but he never formally joined a left-wing organization. He focused instead on the pragmatic goals of building organizations, training activists, and achieving victories that improved people’s daily lives. He worked with many people who did not share his leftist sympathies, but whose struggles and victories helped expand civil rights, workers’ rights, and immigrant rights.

Although he never published the autobiography he spent years working on, Ross did assemble his thoughts on his craft in the brilliant, still-relevant, booklet, Axioms for Organizers, which his son recently republished in a bilingual (England and Spanish) version. One of them is “Good organizers never give up. They get the opposition to do that.” Ross spent his life following that ideal. Our democracy is much better for it.